The Complexity of Neurodiversity: Intersectional Approaches to Understanding Equity

by Kim Shah (She/Her), Lead of the Canadian Chapter of ION, the Institute of Neurodiversity.

There is a need for clarity regarding how neurodiversity relates to other dimensions of diversity, particularly concerning disability and mental health. Additionally, the concepts of “neurodivergent conditions” and “reasonable accommodations” must be weighed against the principles supporting neurodiversity. We need to explain better the complexities and nuances of how neurodiversity interacts with disability and mental health and highlight its essential role within intersectionality frameworks.

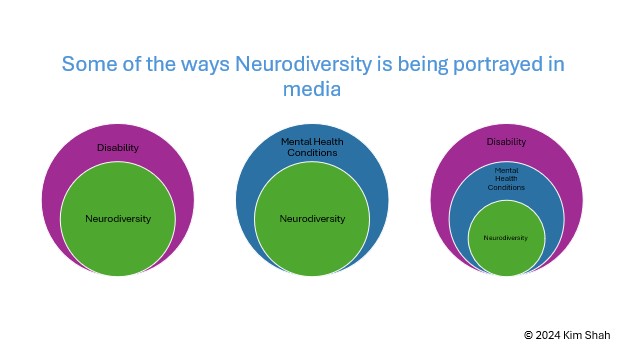

Figure 1: This figure showcases observations of various ways neurodiversity is represented in media in three Venn diagrams, which are conflicting narratives surrounding neurodiversity in public discourse

“Neurodivergent conditions” is a misalignment

In Neurodiversity culture, the term is considered an oxymoron because neurological differences are recognized as part of biodiversity within a complex, evolving ecosystem rather than being seen as a “condition.”

Mental health and neurodiversity are distinct concepts despite both being broad and relevant to everyone. While they relate significantly, they are fundamentally different. The term “mental health condition” tends to pathologize neurological differences, labelling them as disorders or deficits. This perspective contradicts the aim of the neurodiversity movement, which seeks cultural acceptance of neurological differences, emphasizing their evolutionary role in promoting biodiversity in our ecosystem. Thus, combining the term “neurodivergent” with “condition” undermines the essence of the neurodiversity movement.

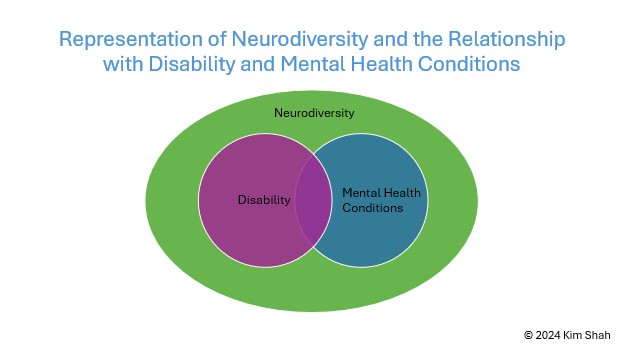

Figure 2: This Venn diagram illustrates the relationship between neurodiversity, disability, and mental health conditions. It emphasizes that neurodiversity is an inclusive concept, supporting the idea that variation in human cognition and sensory experience is a natural process and an aspect of biodiversity.

“Reasonable accommodations” vs accessibility

Another essential aspect is the “Duty to Accommodate” under human rights legislation. Individuals who identify as neurodivergent or have some form of neurodivergence often face challenges when seeking support to navigate outdated systems, such as inflexible workplace processes that do not allow for alternative working styles, rigid work hours that do not account for individual needs or a lack of options for remote or hybrid work arrangements.

These challenges create a paradox as they strive to embrace their complex cognitive and sensory strengths while contending with systems that may not recognize or support their needs. The neurodivergence experience is where cognitive and sensory struggles can happen despite having them as strengths.

Suppose it has been identified that stress brought on by social and environmental factors, such as outdated attitudes or systems, causes the struggles. In that case, the individual is burdened to seek accommodations to function within these outdated attitudes and processes instead of seeking corrective measures to target the outdated system’s inefficiencies and attitudinal barriers.

When organizations implement accessibility measures, as is becoming the case in some regions, the focus shifts from providing “reasonable accommodations” to creating “systemic accessibility.” This shift includes developing comprehensive accessibility policies, ensuring that information and communication systems are accessible—such as distributing meeting agendas and related items in advance—and adopting inclusive recruitment and hiring practices.

This approach emphasizes that accessibility is universal and benefits all individuals, including those with disabilities. By adopting this perspective, there is less emphasis on the obligation to accommodate specific needs as systems are redesigned to be more inclusive for everyone, including individuals with cognitive and sensory differences.

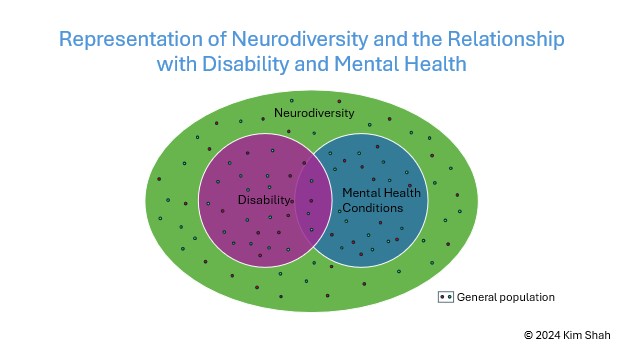

Figure 3: This figure further explores the

connections between neurodiversity, disability, and mental health. It shows

overlapping areas and distinctions between these concepts, helping to clarify

their interrelationships. The dots represent the general population and are

scattered across the diagram.

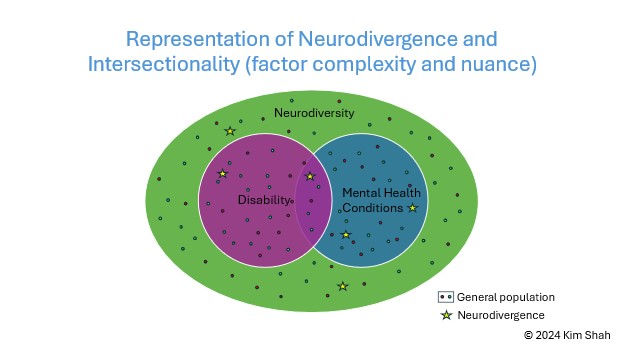

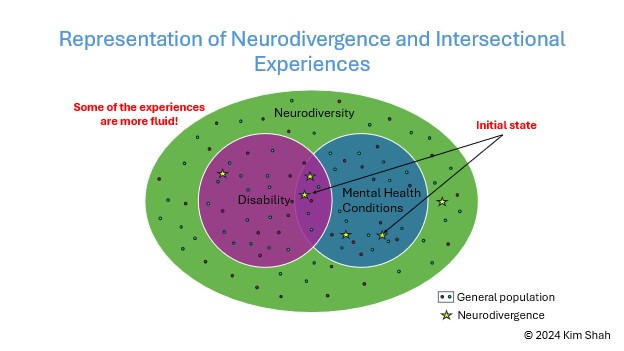

Figure 4: This diagram introduces the concept of intersectionality in relation to neurodivergence. It shows how various factors and identities intersect with neurodivergence, emphasizing the complexity and nuance of individual experiences. The stars among the dots represent individuals who experience neurodivergence and are also scattered across the diagram.

Figure 5: This figure, along with Figures 6 and 7, examines different aspects of the intersectional experiences of neurodivergent individuals. It illustrates how various factors, such as social and environmental influences, interact with neurodivergence and affect how these individuals navigate work and life.

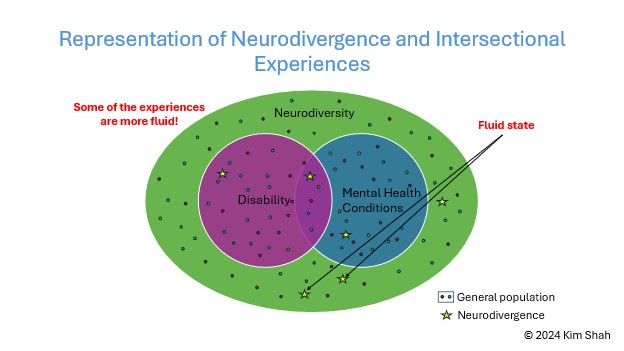

Figure 6: This figure, along with Figures 5 and 7,

examines different aspects of the intersectional experiences of neurodivergent

individuals. It illustrates how various factors, such as social and

environmental influences, interact with neurodivergence and affect how these

individuals navigate work and life.

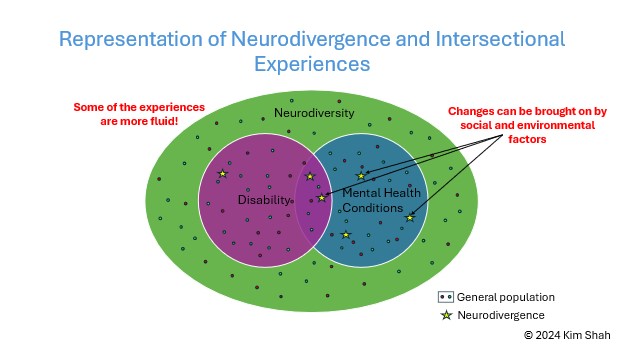

Figure 7: This figure, along with Figures 5 and 6, examines different aspects of the intersectional experiences of neurodivergent individuals. It illustrates how various factors, such as social and environmental influences, interact with neurodivergence and affect how these individuals navigate work and life.

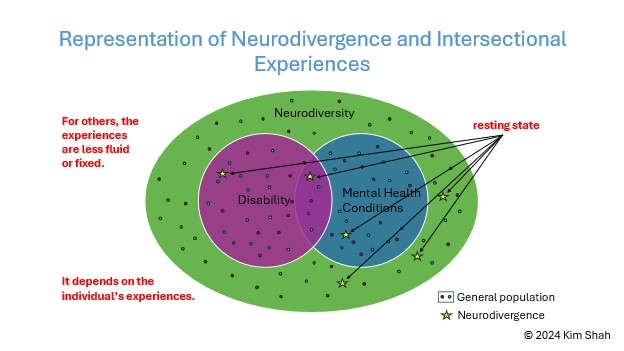

Figure 8: This figure demonstrates less dynamic intersectional experiences and, therefore, reduced impact on some neurodivergent individuals.

Authentic inclusion means everyone

However, there will be times when systemic accessibility measures do not fully meet an individual’s support needs, even when organizations prioritize accessibility within their operations and culture. In these instances, it is crucial to address support needs on a personal level.

Consider the case of a neurodivergent employee working in a large tech company. Despite the company’s implementation of flexible work hours, quiet spaces, and mental health support programs, this individual experiences severe burnout. The standardized measures fail to address their unique needs, such as difficulty with time management, sensory sensitivities to office lighting, and challenges in social interactions during team meetings.

For authentic inclusion, organizations must ensure their approach to accessibility is proactive and systemic but also person-centred, flexible, and responsive. This allows for personalized accommodations that respect privacy while delivering the necessary support to each individual. It is essential to prioritize accessibility but offer specific accommodations when requested, ensuring no one is left behind.

Intersectionality

Neurodiversity is an inclusive concept acknowledging variations in human cognitive and sensory experiences as natural and significant aspects of biodiversity. Neurodivergence—terms such as neurodistinct, neurominority, neurospicy, and neurodivergent may also be used depending on cultural and regional contexts or individual preferences—refers to individuals with cognitive and sensory differences. These individuals experience the world and process information in unique ways.

Neurodiversity and intersectionality offer a comprehensive framework for approaching diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) efforts. These concepts consider individuals’ unique lived experiences, successes and struggles. They help us understand the barriers presented by outdated systems and attitudes, which must evolve to adapt to greater complexity. They also emphasize the importance of human agency in determining one’s own path to success.

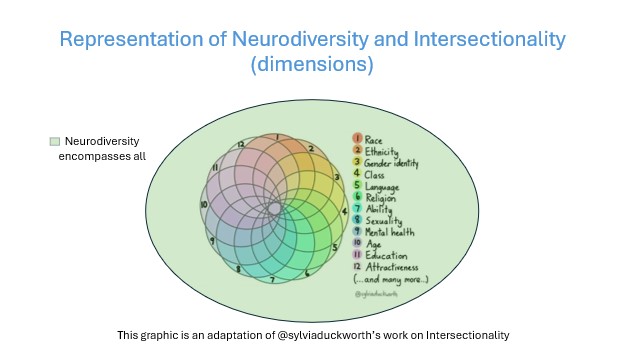

Figure 9: This diagram presents various dimensions related to neurodiversity and intersectionality. It includes factors such as race, gender, socioeconomic status, and other aspects of identity that intersect with neurodivergence. It is an adaptation of Sylvia Duckworth’s work on intersectionality.

Human Agency

The concept of human agency is essential for understanding neurodiversity and its implications for equity. Human agency highlights an individual’s ability to make autonomous decisions, exercise self-determination, and freely express their unique inner experiences. In the context of neurodiversity, this means respecting each person’s right to define and articulate their own identity without external impositions or societal expectations.

This perspective aligns with fundamental principles of freedom of thought and expression, recognizing that neurodivergent individuals have the autonomy to shape their own narratives and make choices that reflect their cognitive and sensory styles . By acknowledging the importance of human agency, we can cultivate a more inclusive approach to neurodiversity that values individual experiences and promotes equitable treatment based on self-determined needs and preferences.

Conclusion

As public education improves on neurodiversity, it will become more apparent that the term “neurodivergent condition” can be unhelpful to the mission. Also, by shifting the focus from “reasonable accommodation” to “accessibility,” we can improve our understanding of the relationships between neurodiversity, disability, and mental health.

To fully embrace human potential, neurodiversity must receive the fair representation it deserves within DEI programs. This ensures that this often-overlooked dimension is valued and included alongside other diversity measures.

Figure 10: This final figure underscores the significance of how various aspects of identity and experience intersect, emphasizing that neurodiversity and neurodivergence should be integrated into this framework.

With thanks to Dan Shepherdson and Audrie Chad for their feedback and valuable input during the development of this piece.

By Kim Shah (she/her), Lead of the Canadian Chapter of ION, the Institute of Neurodiversity.

Kim Shah is a Consultant in the Financial Services industry, with professional experience working for multiple firms within the industry in various roles. She is also actively advocating for mental health awareness, serving as a member of the Advocacy Committee for the Center for ADHD Awareness Canada (CADDAC) and as the Chair and President of the Institute of Neurodiversity – Canada (IONC). Kim and her family live on the traditional territory of many nations, including the Mississaugas of the Credit, the Anishnabeg, the Chippewa, the Haudenosaunee, and the Wendat peoples. The area is also known as the Greater Toronto Area (GTA), home to many diverse First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples. Kim was born on the Caribbean island of Trinidad and Tobago and spent her formative years and adolescence there before migrating to Canada with her family. She identifies as of mixed heritage.